You know the scene by heart because it’s imprinted onto our collective retinas: ghost images of Hopper’s Nighthawks, Coppola’s The Godfather, O’Neil’s Brighton Beach Memoirs...

It’s Brooklyn long before the waves of the yupster invasion. It’s a Bed-Stuy corner of Atlantic Avenue. It’s 1961, three in the morning.

Kennedy has just been inaugurated. The cold war’s dial has been rising steadily from hot to scorched earth. A chimp is getting ready to take its joy ride into outer space. You hear that? That’s Ben E. King’s Stand By Me playing from a transistor radio, even at this late hour. And a third generation Irish kid sits in a diner plated in chrome hearing the tune for the first time.

This is where our story begins. It’s a story that’s New York at its core, but it’s also a story of serendipity, a story of family, and a story that’s just a small part of a much bigger story: one of an industry under-served by history.

But the kid. The kid’s no more than seventeen and looks it despite the inchoate mustache braving it on his lip and the Brylcreem he’s combed through his hair. Having just finished his nightly milk delivery route, he nurses a cup of coffee before heading back home to his young family. Distributing milk bottles is just one of two gigs the kid works. The other is printing house factotum.

He doesn’t know it yet but his life’s design is about to present itself: It rattles the cowbell strung to the front door, waltzes in like it owns the place, and manifests itself in the form of one Herb Arowesty.

Stepping to the counter beside the kid, he orders the usual. While waiting for his two over easy, rye toast, Herb makes small talk, the kind of familiar small talk that can only happen in your own neighborhood when everyone else is asleep and you can admit the Dodgers’ move to another planet still stings, bad. Herb agrees. The kid, when asked, introduces himself as Bill.

“Bill Griffith.”

“Billy the Kid,” Herb says, sideways smile, shaking the kid’s hand like he’s trying to tear it off. Bill takes exception to kid, and to Billy too for that matter, but lets them both slide.

He sees it straightaway: Herb’s the kind of guy who can talk a dog off a meat truck. Or convince a kid to take a day job dressing windows on the spot.

Which is exactly what happened.

Then just like that, the wheel turns: One day helping Herb decorate a gym for a holiday dance turns into another installing signs outside a laundromat, turns into another dressing a window in the city ever-blinking across the bridge. The day job becomes a daily job. Cash, of course, but that suits Bill, and before he knows it, he’s quitting his other two gigs. He’s got dough in his pocket and a prospect for the future in an industry he doesn’t yet know exists.

Most people don’t know it exists.

In a company comprised of two employees, everyone’s a principle. Bill meets the other side of Herb’s coin, Mike Popolow, and they hit it off. Mike takes Bill under his wing, too, and it becomes quickly evident to Bill that Mike is the Creative to Herb’s Salesmanship. These, Bill comes to understand, are the two main ingredients of any functioning display business, and though Bill will work as General Help at Westley Displays for years, he’ll eventually fill the third position in the exhibit builder business model triumvirate: Production.

In the meantime, he does anything asked of him. The trio works out of a tenement-era building that had housed a gin operation during Prohibition. The remnants of the Fed-dismantled still remain strewn about the darker corners of the building. Heated by just a pot belly stove, some days are so cold Bill’s mustache freezes and nearly cracks off his face, just as it’s finding its footing. On raw days in that long first winter, he lugs materials down a hundred yard ramp by hand and loads them into the bellies of trucks parked under the el, then slaps his hands against the numbing. On the dog days of that following summer, there’s nothing he can do but sweat through his shirt.

It’s a living, and one he’s grateful for. He works hard. He and Herb go on routine installs, spraying snow, posing mannequins, scattering oak leaves and white painted branches in the various shop windows dotting the outer boroughs. Mike tends to the finesse jobs in the Manhattan department stores where floor managers want hand-holding and that elusive artistic flair.

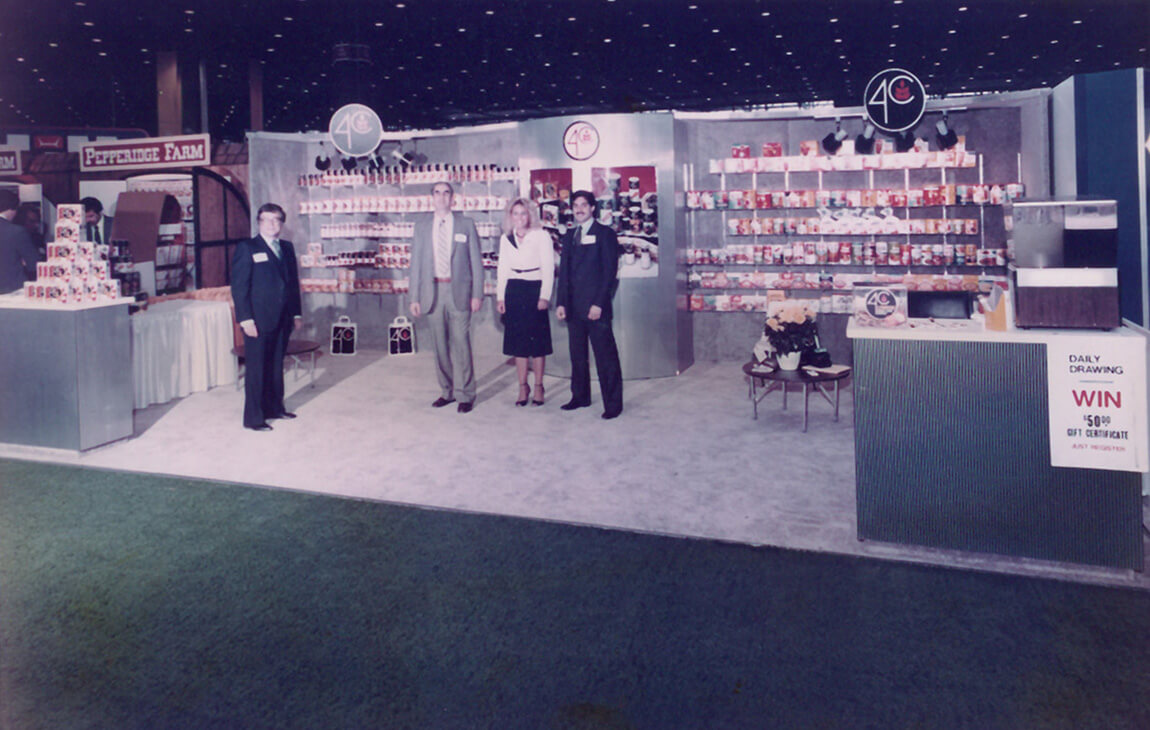

Business is good. Herb gets an itch. It gets better: Some time in the mid-sixties Herb follows his nose along the opportunity trail and by scheme, chance, providence or some combination thereof, the company takes its first tenuous foray into the exhibit industry. Their first exhibit build is for Polish Ham, whose name speaks for itself and whose motto at the time was Put Something Nicer in Your Slicer. Ah, simpler times, indeed.

The project forged a relationship with the client that lasted for over thirty years. It also threw open the doors to the food trade show exhibit industry. In hindsight, all these years later, it’s clear to see that it also established what would eventually become the hallmarks of the company: long-standing client relationships that span decades and a commanding presence with food and food-adjacent (eg. Natural Products, Candy etc.) exhibiting companies.

The formation of the National Association for the Specialty Food Trade (now the SFA) preceded the company’s leap into the field by only a handful of years. As a fellow New York-based outfit, the symbiosis is a natural one, and the company grows in leaps and bounds alongside NASFT and the companies that participate in its events. This all serves as the bedrock for the company as it expands into other exhibiting industries, industries like Dental, Toy, Medical, you name it.

Business booms and it’s a good time to return to our cinematic motif and lean on the passage of time montage device. Close your eyes. Imagine: One exhibit after the other is built, illustrating how the business grows exponentially through the 70s and 80s. Then, a scene from Bill’s marriage. His second child is born. A crate opens on hinges to reveal an early incarnation of the portable display—everything contained inside the shippable wooden crate. Another baby is born. Mike frenetically takes whopping exhibit orders over the phone while hand sketching a custom exhibit for Henry Schein. A ribbon is cut and we pull back to see a new, bigger facility out on the island. Another baby is born. Car keys are passed from Mike to Bill– a ’68 Caddy gifted to Bill when he’s still in his 20s. A hi-lo moves quickly amidst a labyrinth of wooden crates. Another baby. Another new facility a little further out. And so on. All of this is accompanied by a timeless song, of course. The Byrds’ To Everything There is a Season, perhaps, and it’s interspersed with the capital E events of American life: Armstrong doing his moon dance, the fuel crisis, Vietnam, Woodstock, Nixon, CBGBs, Star Wars, Iran Contra, jazzercise, Macintosh, the booming trade show industry. You get the picture (literally).

The montage ends and… well, we all know what happens at this point in every good success story, no? After the Innocence and the Becoming comes the Initial Triumph… and then the Inevitable Low Point. In the standard-issue American biopic it comes in the form of personal tragedy, an external complication, or a combination of both that knocks the hero down inexorably. Things look grim and he must wrestle with the seemingly inevitable prospect of failure and the doubts he harbors about himself and his chances of overcoming his woesome predicament.

Bill’s and the company’s story is no different…

But, alas, the reel is missing, the scene’s on the cutting room floor, the details are blurred. Whatever the case, for our purposes, we can say that there was tragedy and indeed there was a fallout between Mike and Herb, all of which culminates in some approximation of the aforementioned quandaries. When Mike is ultimately ushered out the door, it’s devastating to all involved.

*

But from the ashes rises the phoenix. In 1981, Westley Displays becomes Nationwide Displays and Bill becomes a full partner.

The page turns. The new chapter ushers in new clients, yet another new facility, and Bill’s sons, John and Steve, into the company fold. Working with family comes with its difficulties, of course, but Bill handles it with a sagacity nearing sainthood, watching his sons’ missteps with an understanding, furnished by his Brooklyn school-of-hard-knocks background, that the only way to learn is the hard way, as difficult as that is for both generations to endure. By that same token, he also learns restraint- restraint from micromanaging. He permits his sons and other coworkers the latitude and autonomy to handle their responsibilities themselves. In other words, he learns to trust his workers. He allows them to fail or succeed on their own. He has faith.

By his own admission, Steve’s all thumbs in the shop. But he’s got the gift of gab and proves to be a natural salesman in his own right. When Herb decides to retire, Steve buys him out and becomes President and co-owner alongside Bill. Bill beams with pride as he sees his son guide the company into the modern era of modular exhibits, tension fabric structures, 3D design renderings, and CNC machines, straight through to the current day trends of brand activations, virtual exhibits, and experiential marketing. All this while Bill manages the books, oversees the shop, and transitions into semi-retirement, a man in full.

*

It’s somewhere shortly after Steve becomes a principal that I, your humble narrator and Nationwide Displays’ Creative Director, enters the picture and so, for fear of overly-biased editorializing, I’ll refrain from further elaboration on Nationwide’s recent trajectory except to say that to see what Nationwide Displays is today you only need to take a look at our work or to talk to one of the members of our team or our clients. I can also say that I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to sit down with Bill to discuss his career, the company he’s built, and to have contributed to its history in some small way.

The conversation I had with Bill provided a wider lens through which to see the day-to-day duties we perform in the exhibit industry. His career can be seen as a family man’s American success story set against the backdrop of a (yes, nearly mythological conception of) New York spanning the last chunk of the 20th century and the first of the 21st. But contemplating how a man’s life’s work is inextricable from his time and place prompted me to consider further-reaching connections of the industry in which he worked, an industry that itself is at its heart one built for creating interconnections.

The phenomenon of trade shows, in some form or another, can be traced throughout human history, to the ancient bazaars dating back to 3000 BC. Certainly no one standing behind a rough hewn table at a Souk in ancient Egypt caught the interest of passersby with internally-illuminated tension fabric structures, but for all intents and purposes his objective, and those of his competitors and of the attending public, was essentially the same as it is today. That objective is to peddle and consume wares, certainly, but it’s also about something more elemental: the exchange of ideas, the forging of human connection, the expression of joy for the respective industries in which the purveyors have chosen to work. Seen in this light, the kind of commerce that happens in a trade show or exposition hall is a social act of fundamental importance.

The business of designing and building the environments in which that act happens goes largely unnoticed by the public at large, and so its workers go about their daily business mostly unsung. Once in a while though, for those of us in the thick of it, singing the song is important. Hopefully this one has hit the right note.

And to close, here’s one Bill sang when I spoke to him: “I don’t see my people as my workers, but as my associates. The reality is I would not be where I am without those people. You walk out on a show floor and see what we created… It’s amazing.”

Indeed.

-Joseph Christiana, April 2022